Important Date For Julius Caesar

The Ides of March (; Latin: Idus Martiae, Late Latin: Idus Martii )[1] is the 74th day in the Roman calendar, corresponding to 15 March. Information technology was marked past several religious observances and was notable for the Romans as a borderline for settling debts.[ii] In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

Ides [edit]

The Romans did not number each day of a month from the offset to the last day. Instead, they counted back from three fixed points of the month: the Nones (the 5th or 7th, nine days inclusive before the Ides), the Ides (the 13th for most months, but the 15th in March, May, July, and October), and the Kalends (1st of the following month). Originally the Ides were supposed to exist adamant by the full moon, reflecting the lunar origin of the Roman calendar. In the earliest calendar, the Ides of March would have been the first full moon of the new year.[3]

Religious observances [edit]

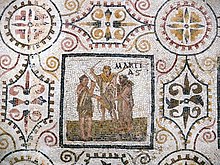

Console idea to depict the Mamuralia, from a mosaic of the months in which March is positioned at the kickoff of the year (first half of the third century Ad, from El Djem, Tunisia, in Roman Africa)

The Ides of each month were sacred to Jupiter, the Romans' supreme deity. The Flamen Dialis, Jupiter's high priest, led the "Ides sheep" (ovis Idulis) in procession along the Via Sacra to the arx, where information technology was sacrificed.[four]

In improver to the monthly cede, the Ides of March was too the occasion of the Banquet of Anna Perenna, a goddess of the year (Latin annus) whose festival originally concluded the ceremonies of the new year's day. The day was enthusiastically celebrated amidst the mutual people with picnics, drinking, and revelry.[five] Ane source from late antiquity besides places the Mamuralia on the Ides of March.[6] This observance, which has aspects of scapegoat or ancient Greek pharmakos ritual, involved chirapsia an old human dressed in creature skins and mayhap driving him from the metropolis. The ritual may take been a new year festival representing the expulsion of the sometime year.[seven] [8]

In the after Majestic menstruation, the Ides began a "holy week" of festivals celebrating Cybele and Attis,[ix] [10] [11] being the day Canna intrat ("The Reed enters"), when Attis was born and found among the reeds of a Phrygian river.[12] He was discovered past shepherds or the goddess Cybele, who was besides known equally the Magna Mater ("Great Mother") (narratives differ).[13] A week later, on 22 March, the solemn commemoration of Arbor intrat ("The Tree enters") commemorated the death of Attis nether a pine tree. A college of priests, the dendrophoroi ("tree bearers") annually cutting downwardly a tree,[14] hung from it an image of Attis,[15] and carried information technology to the temple of the Magna Mater with lamentations. The day was formalized as office of the official Roman calendar under Claudius (d. 54 Advertisement).[xvi] A three-day period of mourning followed,[17] culminating with jubilant the rebirth of Attis on 25 March, the engagement of the vernal equinox on the Julian calendar.[18]

Assassination of Caesar [edit]

In modern times, the Ides of March is all-time known as the appointment on which Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC. Caesar was stabbed to death at a meeting of the Senate. As many as 60 conspirators, led by Brutus and Cassius, were involved. According to Plutarch,[nineteen] a seer had warned that harm would come up to Caesar on the Ides of March. On his way to the Theatre of Pompey, where he would be assassinated, Caesar passed the seer and joked, "Well, the Ides of March are come up", implying that the prophecy had not been fulfilled, to which the seer replied "Aye, they are come, but they are non gone."[xix] This meeting is famously dramatised in William Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar, when Caesar is warned by the soothsayer to "beware the Ides of March."[twenty] [21] The Roman biographer Suetonius[22] identifies the "seer" equally a haruspex named Spurinna.

Caesar'southward death was a closing consequence in the crisis of the Roman Republic, and triggered the civil war that would result in the ascent to sole power of his adopted heir Octavian (later known as Augustus).[23] Writing nether Augustus, Ovid portrays the murder as a sacrilege, since Caesar was also the pontifex maximus of Rome and a priest of Vesta.[24] On the fourth anniversary of Caesar'south decease in 40 BC, afterwards achieving a victory at the siege of Perugia, Octavian executed 300 senators and equites who had fought against him under Lucius Antonius, the brother of Marker Antony.[25] The executions were one of a series of deportment taken by Octavian to avenge Caesar'southward death. Suetonius and the historian Cassius Dio characterised the slaughter as a religious sacrifice,[26] [27] noting that it occurred on the Ides of March at the new altar to the deified Julius.

See too [edit]

- The Ides of March, a novel by Thornton Wilder

- The Ides of March, a film by George Clooney, Fellow Willimon and Grant Heslov

- The Ides of March, a music anthology by Myles Kennedy

- The Ides of March, an American musical group

References [edit]

- ^ Anscombe, Alfred (1908). The Anglo-Saxon Computation of Historic Time in the Ninth Century (PDF). British Numismatic Gild. p. 396.

- ^ "Ides of March: What Is It? Why Do We Still Observe It?". 15 March 2011.

- ^ Scullard, H.H. (1981). Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Democracy . Cornell University Press. pp. 42–43. ISBN9780801414022.

- ^ Scullard, H.H. Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic. p. 43.

- ^ Scullard, H.H. Festivals and Ceremonies of the Roman Republic. p. 90.

- ^ Lydus, John (6th century). De mensibus 4.36. Other sources place it on 14 March.

- ^ Salzman, Michele Renee (1990). On Roman Time: The Codex-Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Artifact . University of California Press. pp. 124& 128–129. ISBN9780520065666.

- ^ Fowler, William Warde (1908). The Roman Festivals of the Menstruum of the Republic. London: Macmillan. pp. 44–fifty.

- ^ Lancellotti, Maria Grazia (2002). Attis, Betwixt Myth and History: King, Priest, and God. Brill. p. 81.

- ^ Lançon, Bertrand (2001). Rome in Tardily Antiquity. Routledge. p. 91.

- ^ Borgeaud, Philippe (2004). Mother of the Gods: From Cybele to the Virgin Mary & Hochroth, Lysa (Translator). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 51, xc, 123, 164.

- ^ Gary Forsythe, Time in Roman Religion: One K Years of Religious History (Routledge, 2012), p. 88; Lancellotti, Attis, Between Myth and History, p. 81.

- ^ Michele Renee Salzman, On Roman Time: The Codex Calendar of 354 and the Rhythms of Urban Life in Late Antiquity (University of California Printing, 1990), p. 166.

- ^ Jaime Alvar, Romanising Oriental Gods: Myth, Conservancy and Ethics in the Cults of Cybele, Isis and Mithras, translated by Richard Gordon (Brill, 2008), pp. 288–289.

- ^ Firmicus Maternus, De errore profanarum religionum, 27.1; Rabun Taylor, "Roman Oscilla: An Assessment", RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 48 (Autumn 2005), p. 97.

- ^ Lydus, De Mensibus 4.59; Suetonius, Otho eight.3; Forsythe, Fourth dimension in Roman Faith, p. 88.

- ^ Forsythe, Time in Roman Organized religion, p. 88.

- ^ Macrobius, Saturnalia 1.21.10; Forsythe, Time in Roman Organized religion, p. 88; Salzman, On Roman Fourth dimension, p. 168.

- ^ a b Plutarch, Parallel Lives, Caesar 63

- ^ "William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act 1, Scene II". The Literature Network. Jalic, Inc. 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ "William Shakespeare, Julius Caesar, Act 3, Scene I". The Literature Network. Jalic, Inc. 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Suetonius, Divus Julius 81.

- ^ "Forum in Rome," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, p. 215.

- ^ Ovid, Fasti 3.697–710; A.One thousand. Keith, entry on "Ovid," Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Hellenic republic and Rome, p. 128; Geraldine Herbert-Brownish, Ovid and the Fasti: An Historical Written report (Oxford: Clarendon Printing, 1994), p. 70.

- ^ Melissa Barden Dowling, Clemency and Cruelty in the Roman World (University of Michigan Printing, 2006), pp. 50–51; Arthur Keaveney, The Army in the Roman Revolution (Routledge, 2007), p. 15.

- ^ Suetonius, Life of Augustus 15.

- ^ Cassius Dio 48.14.ii.

External links [edit]

- Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, The Life of Julius Caesar

- Nicolaus of Damascus, Life of Augustus (translated past Clayton M. Hall)

Important Date For Julius Caesar,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ides_of_March

Posted by: wardposs1950.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Important Date For Julius Caesar"

Post a Comment